I hope you enjoy this, for those of you who are interested, the script I had in front of me is printed below.

So the extent of the

feedback I’ve had on this one is that it didn’t work on one guy’s

computer running 64-bit Windows, so if anyone watching this is

running this so-called operating system, I would appreciate if you

would try to run it and see if it works.

Also, regardless of

what operating system you’re running, I would recommend that you

play Homogeny and Monotony, the prequels to this game, and if you’re

especially interested take a look at their associated symbolic

analyses.

The game does open

with the word “regret”, which directly follows on from the ending

scene of Banality, which ends with the final title card “regret”.

This is in reference to the central theme of Monotony, which is the

character trying to reconnect with their estranged peers.

If you watched the

symbolic analysis of Banality, you might recall that the bed

represented the character’s comfort zone, which it still does in

this game. The character is pressed against their bed, sort of

symbolizing that they are trying to get back into their comfort zone

– again referencing the idea of reconnecting and becoming “normal”

again.

The character’s

opening line is “If nothing else, Sisyphus was happy”. For those

of you who don’t know who Sisyphus is, he was a mythological greek

guy who was cursed to roll a boulder up a hill, only for it to roll

back down, leading to the fairly popular phrase, “One must imagine

Sisyphus happy”. The implication here is that despite the otherwise

lack of real substantial content behind social activities, it’s

easy to indulge in.

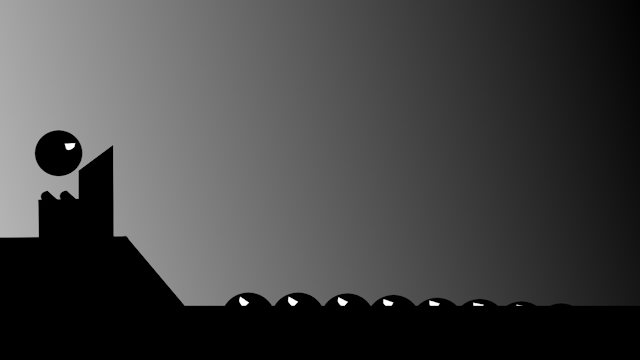

To be honest, I

regret not making this area more clear in terms of direction- you are

actually meant to touch the people in this one. Touching the people

plays the reverse of the sequence in Banality, where the metaphorical

representation of you is being raised up on a platform rather than

descending. However, this time it breaks when you get to the top, and

you fall down. This represents the idea that it’s impossible for

the character to ever return to normalcy, and they fall back down

despite their best efforts.

The term

“desperation” as shown on the screen should be fairly

straight-forward, it makes reference to the idea that the character

is desperate to re-connect with the aforementioned estranged peers.

Something I probably should have pointed out a bit of time ago- the

character is intended to have strange or otherwise awkward speaking

patterns, to sort of exemplify how they are so different from other

people that they literally cannot relate to them even on the most

basic terms of language. To be quite honest, “what a terrible

purgatory” is totally flavour text.

This scene shows the

character getting up from the platform, so obviously it’s implied

that the player is now controlling the metaphorical representation of

the character from the broken platform beforehand.

The character is

then confronted with a button and door puzzle, like in Banality and

Yet Another Puzzle Game. It’s meant to create the idea that the

character is able to look at the things separating him from the other

people, solve them easily, but still finds himself inexplicably

distant from them when they start running after the door opens.

At this point, the

other person has escaped and the character is left to find another

route around the same obstacle, which in this case is over this

building here. Also, the music at this point becomes somewhat glitchy

and distorted, which again is mainly to convey the aesthetic that the

character’s mental state isn’t good or orderly.

This next sequence

is fairly dense in terms of meaning in that you have the title card

with the word “quickly” repeated on it, the shaking screen and if

you don’t pause then you will eventually come to the end of the

background. The title card “quickly” is designed to create a

sense of urgency that the character must continue to try to

re-connect with people, the shaking screen represents the character’s

unsteady or ineffectual effort to keep trying, and the short peak of

the end of the background represents the idea that the character, in

the process of their efforts, has seen things which do not make sense

to them in the same sense that a three dimensional object doesn’t

make sense to a two dimensional creature.

The character is not

present at all in the bedroom sequence, which represents the idea

that they have abandoned their comfort zone totally.

The title card

“broken brilliance” is a term that has become so removed from its

origin in my mind that there is no point trying to explain its

origin, but it is in itself a fairly poetic concept. This will be

left as an exercise to the viewer.

The colourful

glitchy artifacts around the screen again represent things and

concepts which don’t make sense to the character, and were never

apparent or visible in their own “world”. The things they

interact with would have never contained things like this, as

demonstrated in the previous games being entirely monochromatic. This

is linked with the term “broken brilliance”- the “game” is

broken, but it’s worth it for the sake of its visual appeal.

The term “keep

moving” is fairly direct in terms of meaning, it’s a direct

instruction for the player to continue moving towards the end of the

level.

The ending text is

similarly very straight-forward in its meaning.